I assume you will go to work tomorrow. I assume your day will go well.

Yes, I know. You may have a micromanaging boss and team members who don’t respond to your e-mails. If you’re a nurse, patients may die and you could miss lunch.

But when I say “things will go well,” I’m talking macro here. You’ll drive to work, including under bridges, and the bridges will hold up. You’ll enter the building and take for granted that the building is up to code. You’ll sit in your chair, fully confident that all the screws are screwed in tight.

You’ll go home that evening.

On August 5, 2010, 33 miners report for work at the San Jose Mine in northern Chile. They, too, assume their work day will go like it always does. (One miner descends without his helmet. I’ll get it at lunchtime, he thinks.) They, too, assume they’ll be back out that night, drinking in the local bars.

They know that mining is dangerous. They pride themselves on facing down the risks.

Inside the mine, they often hear the thunderings of falling rock. But on August 5th, one of the crews tells their boss “the mountain is making noises you ordinarily can’t hear that far down. . . . The thunder can be heard in every corner of the mine, and it’s causing a sense of worry to spread through the passageways—and also a sense of denial.”

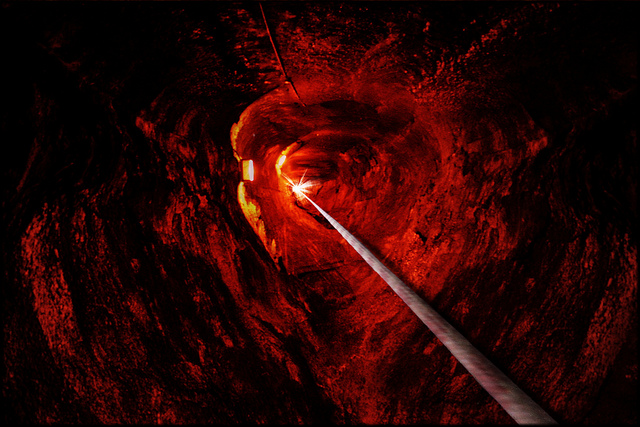

The mine is 2200 feet deep, its stacked caverns connected by The Ramp, a five-mile-long roadway that spirals down into the hot depths of the Earth.

Foremen have noticed significant cracks in the Ramp recently. When they complain to the mining company, the owners place mirrors in the cracks, to detect further shifting. One older miner keeps a notebook, jotting down disturbing developments: water leakages, “falling material, tunnel walls detached,” only to be called a coward by the owners.

On August 5th, the crew hears all that thunder. Some of them vote to go up to the surface. But then they stay on.

You can read the movie-disaster details of what happens next in Deep Down Dark by Hector Tobar.

Deep Down chronicles not only the long sweaty suspense of the 33 miners, but the stomach-drop reaction on the surface as people up there discover “something’s happened at the mine.”

You, the reader, know all along that the 33 miners are alive. But everybody else is strung tight with suspense. Actually, so are you, wondering whether they’ll search against all hope, or seal off the mine and get on with some national mourning.

Family members gather and establish a makeshift campsite called Camp Esperanza (Camp Hope). They plead for the rescue of their family members.

Meanwhile, down below, the men cope with their own sense of doom, with the food supply meant to sustain “an entire shift alive for two days”, with the fingernails of one personality scraping against the chalkboard of another. One miner has way too much ego to fit in a mega-mine. Another normally drones on too long with his boring stories. But, while trapped together, the miners are all too glad to be distracted by his “radio voice” explaining the intricacies of Chilean labor law, and the benefits their widows will receive in case they don’t make it out.

Tobar’s book traces the flame of hope, burning bright one day, nearly snuffed out the next. This world-famous disaster was Chile’s worst moment and its best.

Photo credit: Now and Here via Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Oh boy….. I cannot abide imagining the cannot-get-out-of-here.

Arg…..so much claustrophobia possibility.

I probably would be fascinated by all the human story angles, however.

I think you would like the human angle.