In all my random reading, how’d I end up with a book about a land stricken by apartheid the same week as the riots in Charlottesville? As I eyed the book on my shelf, I wasn’t sure I wanted to take on 312 pages of racial problems and blaming whites.

Nevertheless, I forged on into Alan Paton’s Cry the Beloved Country, in which the Reverend Stephen Kumalo, a native (read: black) priest travels from the hinterlands to the city of Johannesburg, searching for his son. The priest and his wife (must be an Anglican priest) haven’t heard from the boy in a disturbingly long time.

The search leads him from friends to friends of friends, to friends of friends of friends. “He was here, but now he’s not,” people tell Kumalo. As the father follows the son’s nearly-cold trail, it’s the things people won’t tell him that build Kumalo’s sense of doom.

”

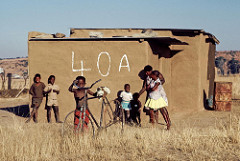

Johannesburg is full of natives. They pour in from the countryside, from valleys where the soil is exhausted, the cattle thin. They come to work for wages, which aren’t much.

Meanwhile, city life cuts their ties to the tribe, to culture and tradition. And they get into trouble.

Paton’s book, written in 1948, portrays a nation that already knows its racial policies aren’t working. But no one can agree on a solution. The English have their idea, the Afrikaans theirs. To the ladies at their tennis clubs, the natives are nothing but a noisy horde that “hangs about on the corners.”

They fear the natives, because the natives outnumber them.

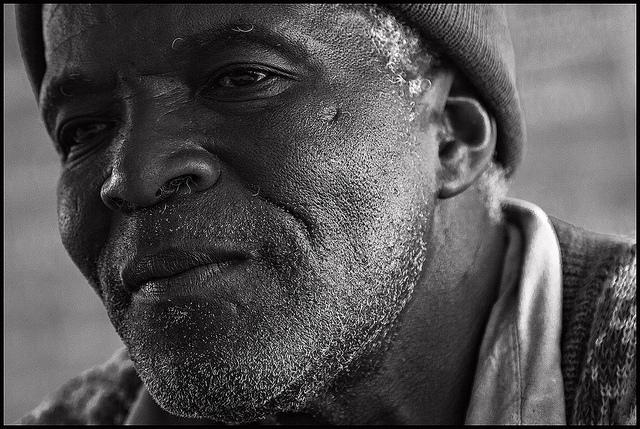

As for the natives, Kumalo’s friend tells him, “Because the white man has power, we too want power . . .. But when a black man gets power, when he gets money, he is a great man if he is not corrupted. I have seen it often. He seeks power and money to put right what is wrong, and when he gets them, why, he enjoys the power and the money. Now he can gratify his lusts, now he can arrange ways to get white man’s liquor, he can speak to thousands and hear them clap their hands. Some of us think when we have power, we shall revenge ourselves on the white man who has had power, and because our desire is corrupt, we are corrupted, and the power has no heart in it.”

Paton describes a beautiful land, but with all these troubles, and with what Kumalo finally learns about his son, “This is no time to talk of hedges and fields, or the beauties of any country. Sadness and fear and hate, how they well up in the heart and mind, . . . The sun pours down on the earth, on the lovely land that man cannot enjoy. He knows only the fear of his heart.”

Photo credits:

Unshaven man: anjan58 via Visualhunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Children: United Nations Photo via VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Group of men: United Nations Photo via Visualhunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Leave A Comment