The summer of 2020 was a season of racial repentance.

Or, at least it was supposed to be. White people like myself were supposed to kneel, to post creeds about learning and trying harder and looking inward to see where our poisons lurked. Surely they were in there somewhere.

I’m not sure I’ll ever get around to all that.

For one thing, the fever pitch seems unwarranted. It’s one thing to say, Black people have problems that white people don’t get. It’s quite another to say, This is the worst it’s ever been. How can this be so when I’m surrounded by whites who signal like neon billboards that they would never commit offenses they’ve read about in the history books? Why are these careful people kneeling and confessing and letting themselves be “condemned for intolerance so deeply buried they [are] not even aware of it themselves,” as Peter Hughes writes in Quillette? Why do they interrupt themselves in the middle of a meeting and ask out loud, Can we still say that?

It all reminds me of Robert Hughes’ grand history of Australia convict roots, The Fatal Shore.

Hughes documents Britain’s massive experiment on its criminal class. The nation’s prisons were full to bursting, with the overflow doing time on ships bobbing in the harbor. What about transporting all those thieves and poachers to an unknown continent far across the world?

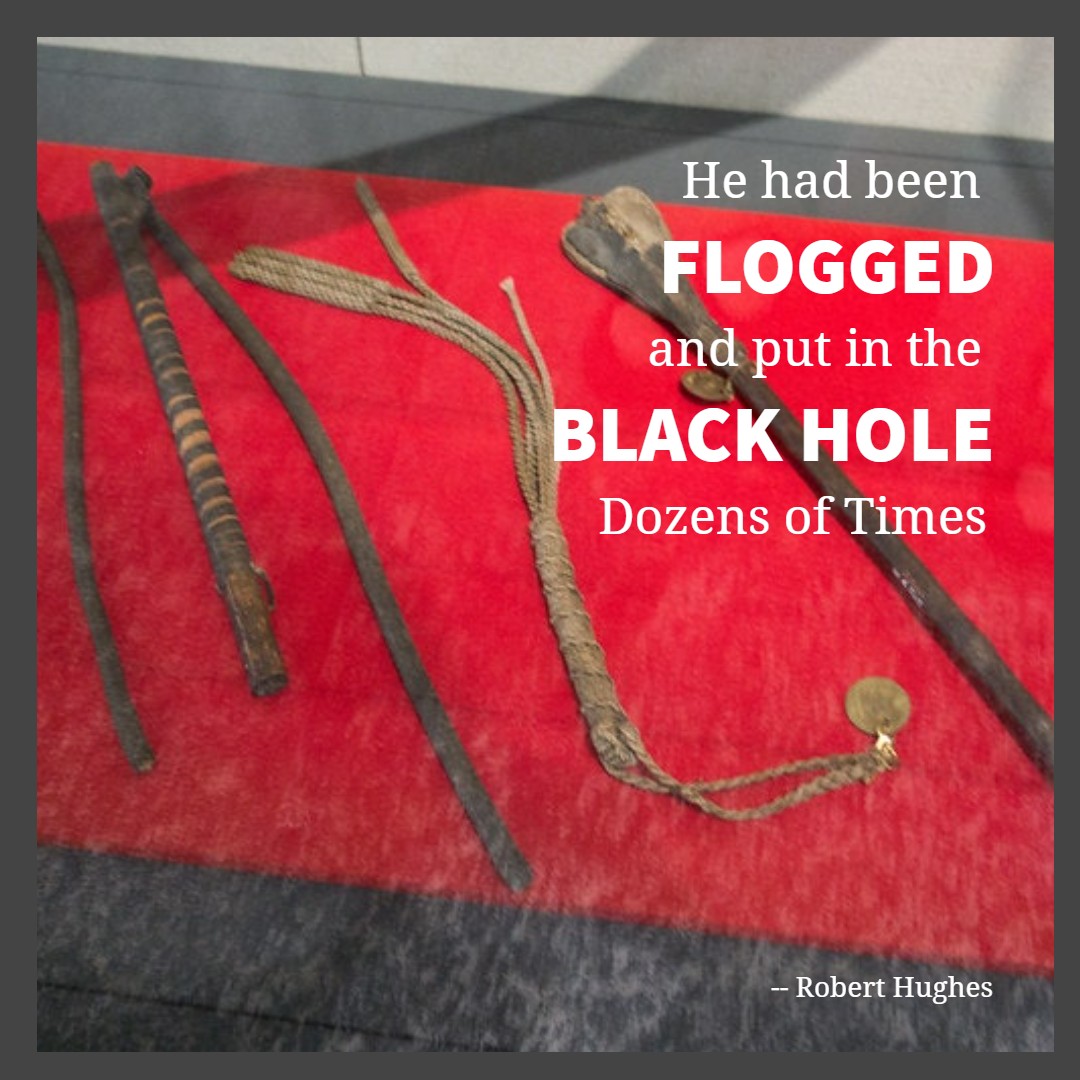

To be sure, a population infused with wrongdoers is hard to control. None of them wanted to be in a strange and distant land, even if it saved them from the hangman’s noose back in England. The especially rebellious staged mutinies on ship, or escaped on land, or stole sheep or bread or weapons. Their extra crimes earned them lashes with a cat-o’-nine-tails. In fact, flogging was so common in Australia that children mimicked it in the play-yard.

Over the 50-60 years of convict transportation, the country’s wardens came up with ever more methods for breaking the hard cases. Eventually a convict might get the lash for “mislaying his shoelaces,” or “walking along waving a twig,” or “having a tamed bird.” One hundred lashes. Oh, and tack on seven days in chains.

It’s not that the punishment grew worse. It’s that the punishable offenses grew pettier.

So here we are, wrought up over race in America. As Bill Donohue points out in Newsmax, speaking out loud about our porous southern border is racist; a remark from Megyn Kelly that blackface was once a common Halloween costume is racist; complaining about the policies of a black president is racist.

As we struggle to filter every word we say, words that were OK only last week, we find our selves “flunk[ing] the wokesters’ ideological purity tests.” Not only have the race wardens found new ways to flog us — lost jobs, public harassment — but their “ever-more exacting demands for tolerance . . . can never be satisfied.”

I wonder what it could take to get me to kneel, and recite creeds, and read the anti-racist books continually popping up on my screens. I guess I’d have to believe that “this is the worst it’s ever been.” I’d have to believe I’m one of the people who would never have made those mistakes, and I doubt that’s true. I’d have to believe that a perfect, nobody-gets-offended world is possible.

But I don’t. Prejudice is just one version of an ever-present human problem, that of making wrong assumptions about people. I’ll be catching myself doing that until the day I die.

I also agree with Rod Dreher that this game is about power. “All the incoherent inconsistencies that [the woke] spout out are not to persuade. They are to shame and conquer.”

Photo credit: quinet on VisualHunt / CC BY

Image created on Snappa.com

Leave A Comment